Omar W. Nasim

Historian of Science

Omar W. Nasim

Historian of Science

Welcome …

I am a professor of the History of Science at the University of Regensburg, specializing in the visual, cultural, and material histories of modern Western science.

My research shifts focus from scientific end-products to the painstaking, often invisible labor behind them. I investigate the mundane tools and bodily practices—like drawing, photography, and even the use of chairs and ink—that shape knowledge production. By uncovering these marginalized elements, my work challenges deep-seated divisions between mind and body, objective and subjective, and manual and mechanical work.

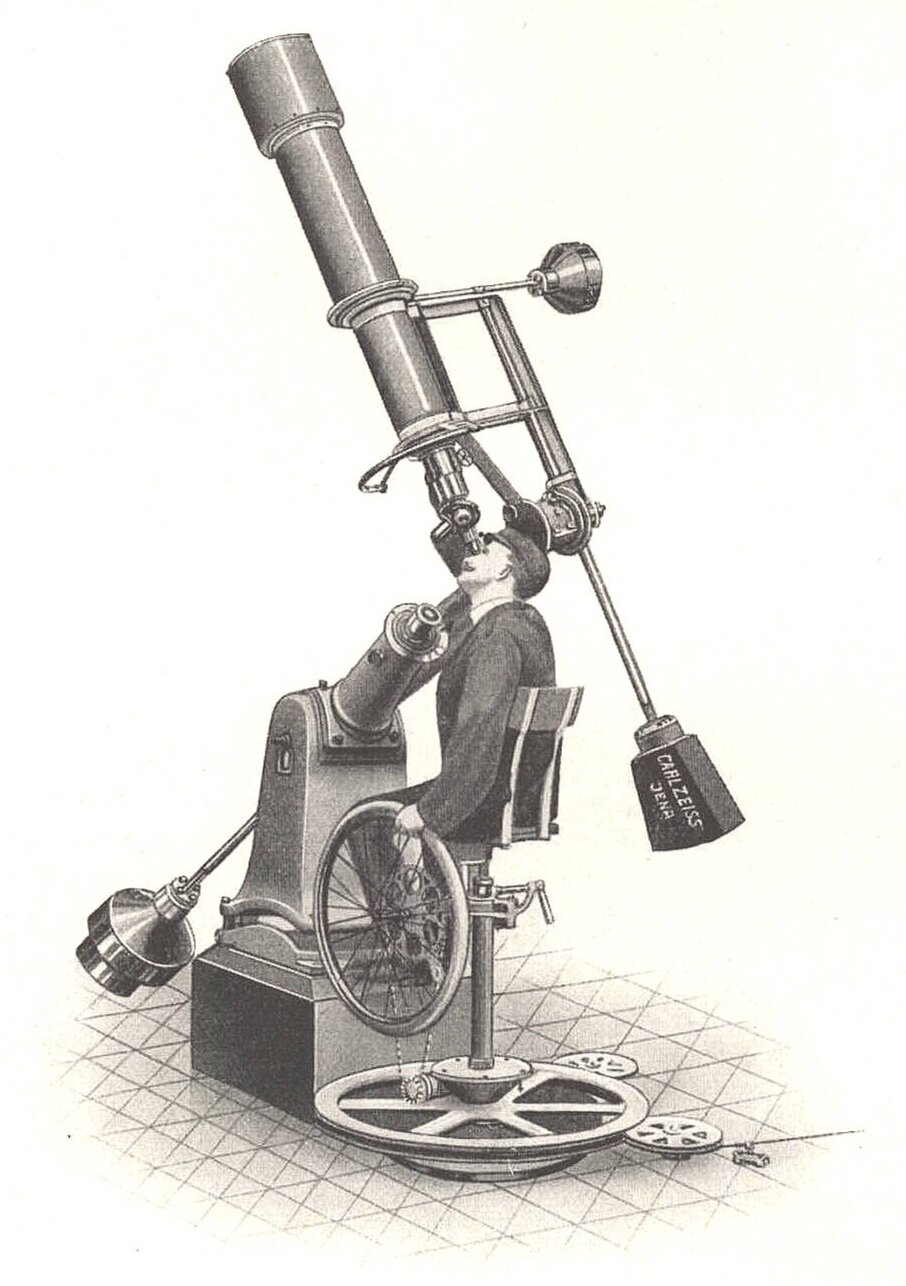

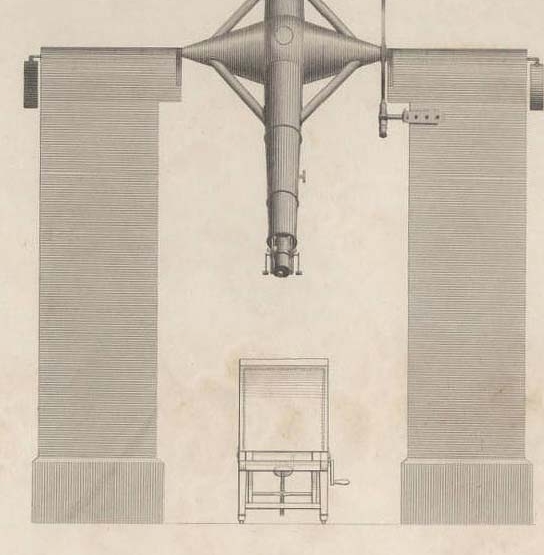

I explore 19th- and 20th-century observational practices in astronomy. My recent monograph examined the cultural history of the astronomer’s chair, while my current project re-examines astrophotography through the lens of manual work with ink. This approach reveals the hidden cultural assumptions embedded in scientific routines and offers new perspectives on science's role in society. Currently I am writing a monograph on the history of astrophotography from the perspective of material culture.

the astronomer’s chair

MIT Press, 2021

the astronomer’s chair

MIT Press, 2021

THE ASTRONOMER’S CHAIR

A Visual and Cultural History

The Astronomer’s Chair offers the first cultural history of seat-furniture in science. It analyzes 19th-century adjustable observing chairs for telescopes, linking their design and imagery to broader bourgeois, imperial, and racial ideologies. The book argues that these chairs were not merely functional but were embedded in a **moral economy of posture**, where a specific seated stance represented Western masculine science as both comfortable and civilized. This posture was defined in opposition to depictions of cross-legged “Oriental” astronomers, which for Western audiences signified a primitive form of scientific labor. By connecting visual and material culture, the study reveals how assumptions about gender, race, and empire became physically built into scientific tools. It concludes by extending this framework to reinterpret 20th-century objects, like Freud’s couch, thereby decolonizing the hidden histories of scientific furniture and its enduring impact.

Reviews

“Drawing on rich, compelling sources, The Astronomer’s Chair is an original, provocative, and fascinating work.”

—David Kaiser, Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science, MIT

“This creatively illustrated study by an eminent historian uses a seemingly mundane theme, depictions of astronomers’ seating, to reveal with startling insight and expert craft the complex cultures of comfort, attention, and discipline that governed nineteenth-century stargazing.”

—Simon Schaffer, Professor of History of Science, University of Cambridge

“The Astronomer’s Chair takes us on an interdisciplinary journey through the history of science, design, imperialism, and material culture. With this book, Omar Nasim models thrilling new directions in intellectual inquiry.”

—Aviva Briefel, Edward Little Professor of the English Language and Literature and Cinema Studies, Bowdoin College

“A fascinating book that underscores how, in visual culture, it’s often pictures of those who explore science that best communicates the nature of their work.”

—Marvin Heiferman, curator and author of Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe

“The Astronomer’s Chair brings together disparate bodies of literature—from histories of fatigue science and hygiene to scholarship on decorative arts and postcolonial readings of Victorian travelogs—in a fluid and readable way. The book is beautifully illustrated, and Nasim has done an impressive job tracing the history of specific astronomers’ chairs back to their design and workshop production, the kind of object-based research that is often hampered by incomplete archives. It is an excellent example of the kinds of insights that can result from an interdisciplinary cultural history and illustrates how looking at mundane objects can reveal illuminating entanglements between science and society more broadly. I can also imagine this book being a useful teaching tool on a variety of subjects, particularly for teaching students to combine close reading and visual analysis, showing them that scientists are “products of their culture” and not isolated from the social worlds of which they are a part .”

—Sarah Pickman in H-Material-Culture, H-Net Reviews.

Current Projects

Current Projects

ornamental mind

optical illusions and design

This is an intellectual and cultural history showing how a set of assumptions initially formulated about ornamental artefacts and images--coming in from all over the world into Western Europe during the early nineteenth century--informed and shaped the use of visual images in the praxis of the Human and Mind Sciences later in the same century. I explore how an extensive discourse on the ornamental arts was a source of motivation and grounding for the use of images as revealing something unique about the operations or disorders of the human mind.

The astronomer’s chair

The Astronomer’s Chair: A Visual and Cultural History (MIT Press, 2021) looks--for the first time--at the role of chairs in the history of science. With a focus on the astronomer's observing chair in the nineteenth century, I open up a host of issues touching on what images of seated scientists meant in face of heroic science; what a scientists' posture indexed to audiences; and what scientists from other cultures who did not use chairs imply for Western audiences in the nineteenth century. In addition, the chair in astronomy is a history about modernity and professionalization. It is a story about observation and imperialism as much as it is about how postures and chairs afforded a particular kind of science over others.

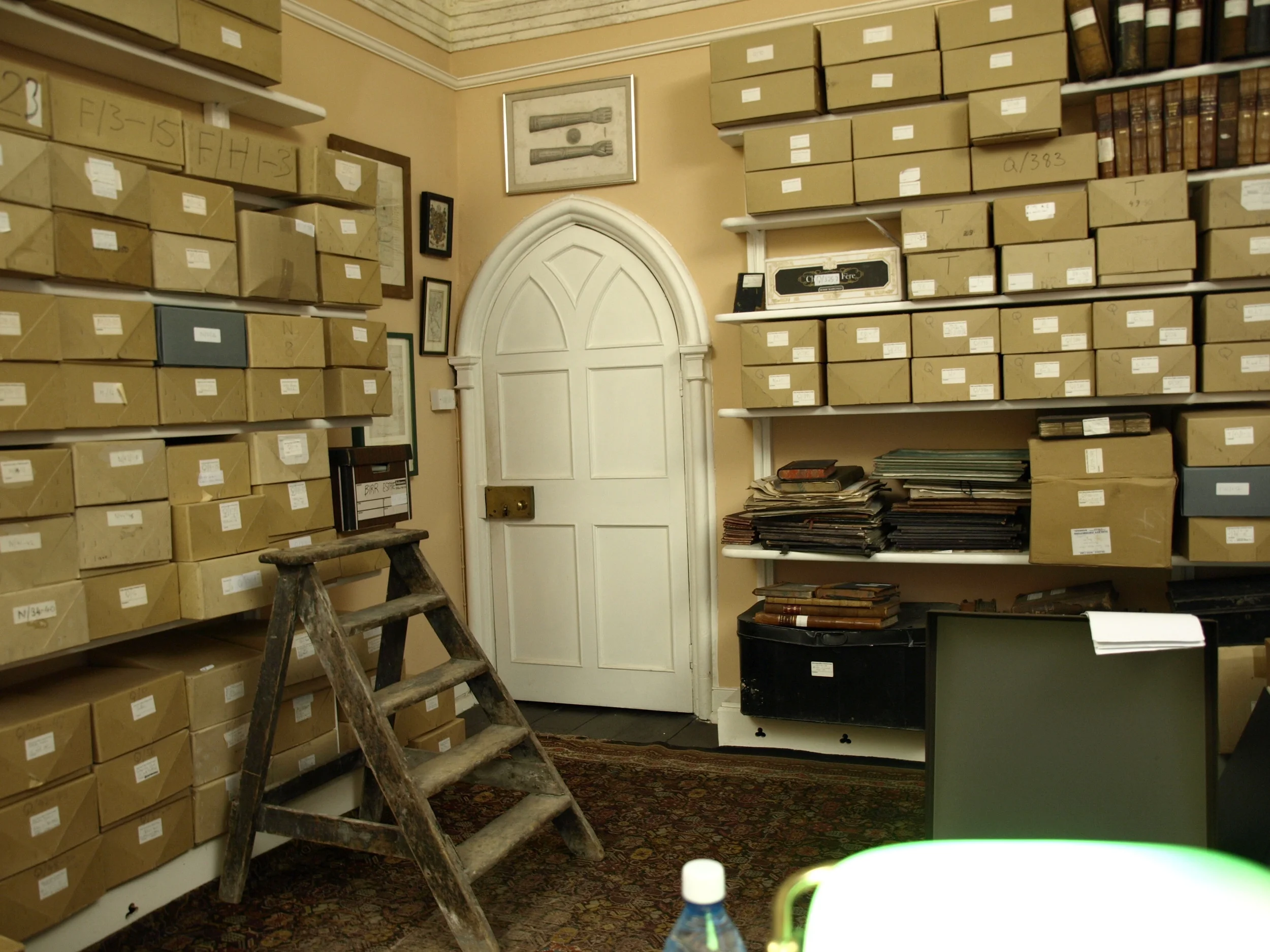

Dfg-Funded Project: Astronomy’s Glass Archive

This project combines photographic history and history of science and technology to interrogate the role and importance of photographic materials and practices in shaping and re-configuring astronomy in the era of glass plate photography. This new research moves beyond contemporary scholarship by revealing a view of how photography was used by scientists in their day-to-day practices, and how standards were established for manufacture and use of glass plate photography in astronomy and more widely. We aim to show that the “information” contained on these glass objects extends beyond the image. Instead of taking representation for granted, we examine how it was materially and technically achieved.

My Books

My Books

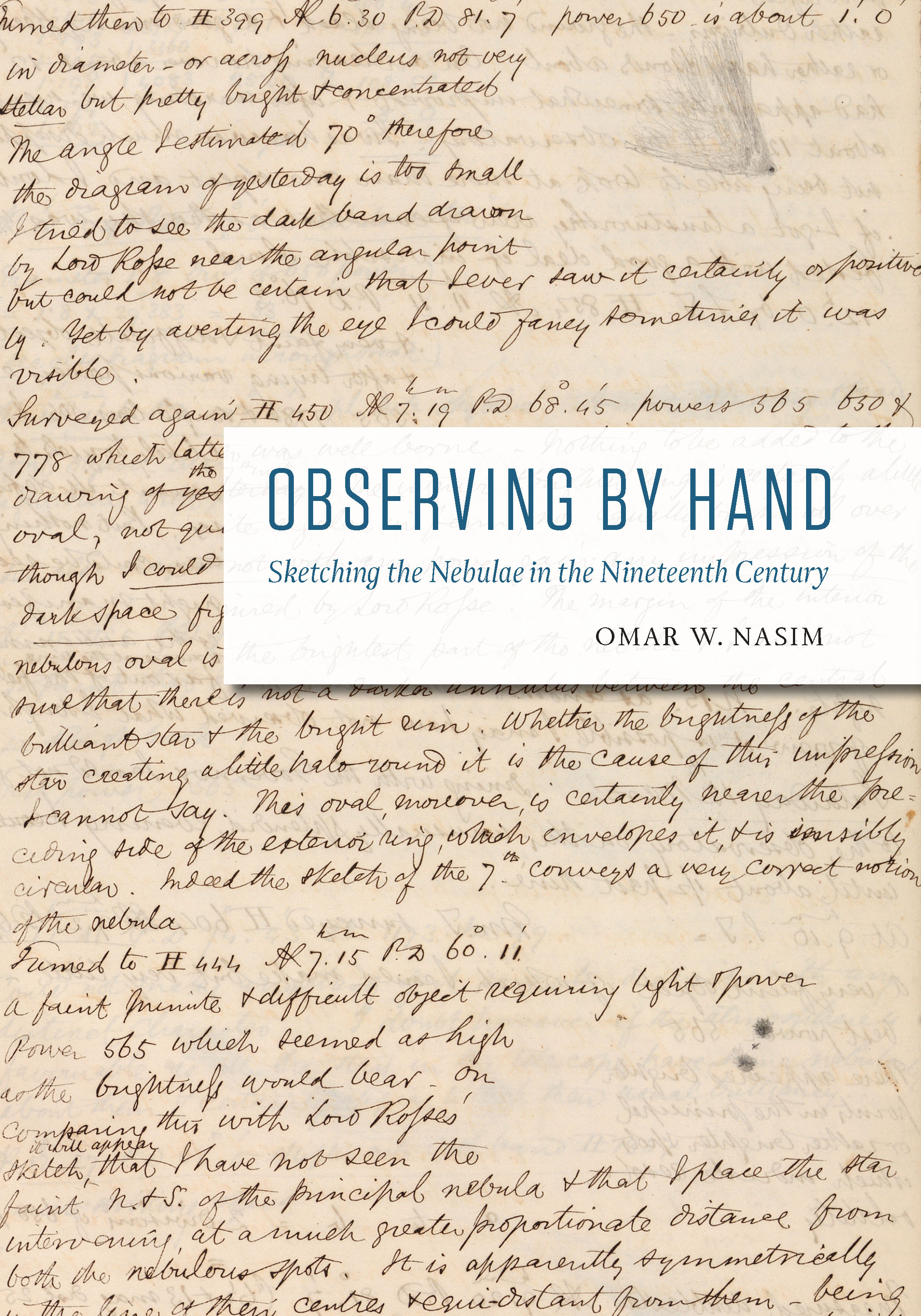

observing by hand

sketching the nebulae in the nineteenth century

A book about what the act of drawing contributes to knowing and seeing in an observational science like astronomy. I access these connections and contributions through a close study of unpublished and private observing books belonging to nineteenth century astronomers. The story told is as much about how mysterious and ambiguous objects like the nebulae were visualised and stabilised as phenomena as it is a story about the role of paperwork in science. In the end the book attempts to raise the status--through a close study of sketch-making practices--of instruments such as a pencil and paper for the history of science.

This book won the prestigious HSS Pfizer Award for Best Scholarly Book in the field of the history of science. For more click here

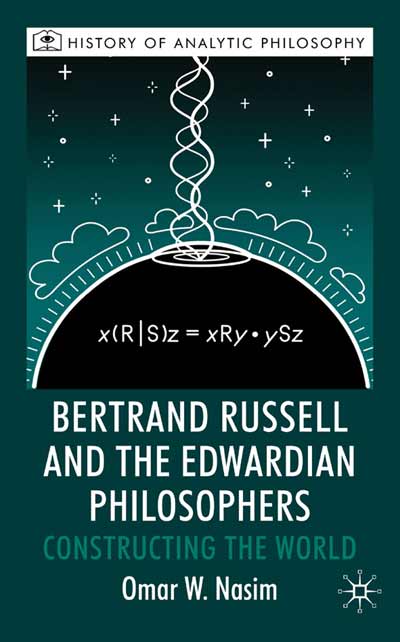

bertrand russell and the edwardian philosophers

constructing the world

This award-winning book deals with the ways in which Bertrand Russell was influenced by a major controversy that raged within English philosophy at the beginning of the 20th century. It shows how philosophers--some who have now been forgotten--helped Russell to give shape to his solution to the problem of the external world. Notions as central to analytic philosophy as 'sense-data' and 'logical construction' are re-interpreted in the context and framework of Russell's direct engagement with an Edwardian controversy. Embedding Russell's philosophical work from the period in this way also connects it to currents in late nineteenth century psychology and mathematics.

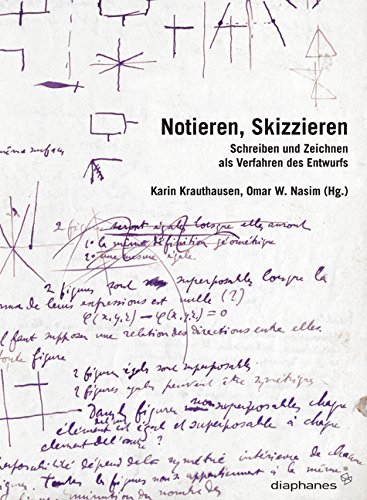

Notieren, skizzieren

schreiben und zeichnen als verfahren des entwurfs

A collection of essays in German that I co-edited (with Karin Krauthausen). This interdisciplinary collection brings together essays on note-taking and sketch-making practices. Leading scholars in the fields of comparative literature and art, history of science and mathematics contribute original essays addressing the connection between these practices and creativity, design, and knowledge-production. The book also contains a transcription of an exclusive interview with Hans-Joerg Rheinberger.