Welcome …

… to my webpage. As the Professor for the History of Science at the University of Regensburg (Germany), I’ve authored numerous articles, edited collections, and of three monographs, two of them award winning. I am a specialist in the visual, cultural, and material histories of science and technology in modern Western Europe, USA, and Great Britain.

My interdisciplinary work critically details knowledge acquisition and production as painstaking labor that is implicated in wider moral economies. It purposefully shifts attention from resulting end-products in science to meticulous processes that go into their production, only to recast historically interlocking socio-cultural relationships between result and process. This shift draws much needed attention to the significance of what we take for granted in the laborious practices of knowledge-making. By uncovering, that is, the historical significance of the mundane and marginalized, the subjugated and invisible, we do more than merely fill in the gaps. We also gain new and critical vantage points on the usual suspects of more standard historical narratives; vantage points that reposition us to ask new questions like, what are the routine practices of erasure or making invisible in the histories of science and technology? Besides my research having non-reductionist implications for how historians engage with objects, design, sites, images, text, media, networks, and concepts, it, much more fundamentally, shows time and again how permeable certain philosophical divisions, which continue to be so important to western industrial societies and innovation cultures, in fact are; divisions such as knowing and being, mechanical and manual, objective and subjective, self and other, analog and digital, headwork and handwork, mind and body. In this way, history is timely, impacting and shaping how we frame and reframe current social and cultural debates and challenges about the place of science and technology in a world still reeling with their profound but all-too-human impact.

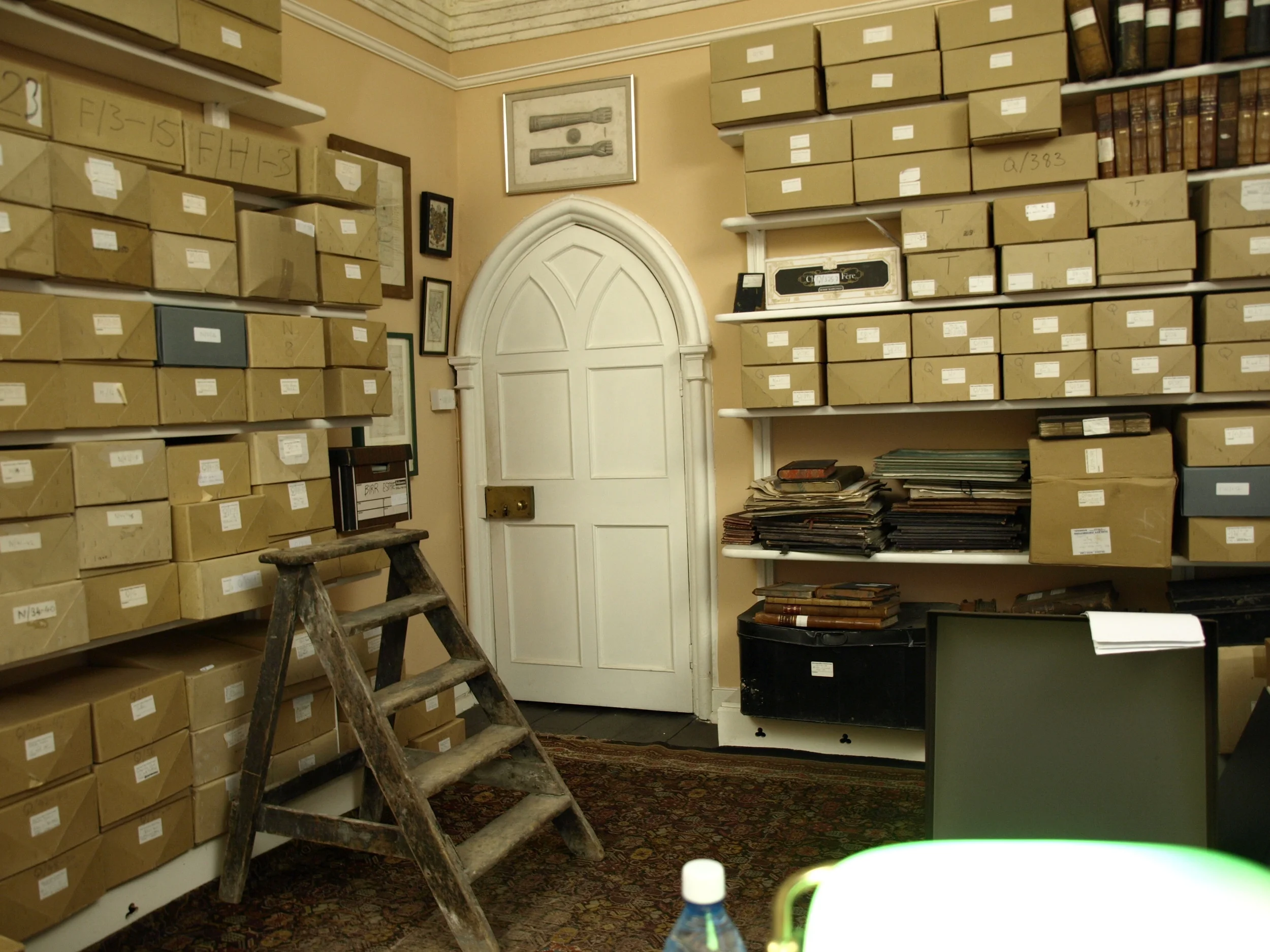

More specifically, my research centres around observational and visualization practices in the history of nineteenth and twentieth century science (especially astronomy), whether these take the form of hand-made drawings or photography. Underwriting this interest, however, is my fascination with the invisible and neglected in the history and philosophy of scientific practices. Typically, when one broaches visual practices, the focus in historical and philosophical accounts remain the eyes, some ocular instrument (like a telescope or microscope), and published images. However, what remains invisible and neglected as a result of this dominant focus is entire layers of supporting conditions that make such practices possible in the first place; such as paper, glass, pencils, ink, notebooks and even chairs, not to mention the tactility of these materials and the role of the hands’ gestures and performances. I am interested in the painstaking labor of science, where comfort and epistemology come into rapport and where assumptions about standards and best-practices emerge. It is in this back-stage-work that one finds lurking in the very furniture and cabinets of science, assumptions about the Other—whether non-western or emotional—that condition these processes of scientific work. So for instance I have recently completed a monograph on the cultural history of the astronomer’s observing chair, disclosing nineteenth century cultural and imperial assumptions built into its very image and function. At the moment, I am working on the history of astrophotography, again, from the perspective of the hands and ink, two things typically disassociated in photo-histories.